Machen's Indebted Children

Reformed Seminaries and Federal Student Loans

About a year ago I ran a piece about how various Reformed seminaries had taken significant federal financial aid that was made available during the COVID-19 pandemic. Millions of dollars went to schools, some of which came with potentially problematic conditions imposed by the federal government.

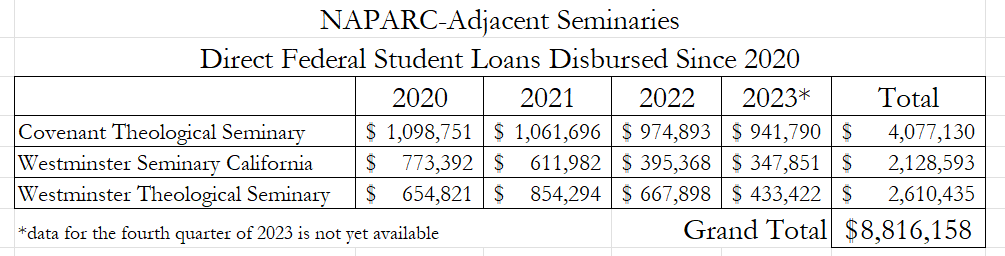

In that article I hinted at another piece of the federal aid puzzle that also affects seminaries, though I did not expound on it in detail—federal student loans. This is an issue that involves fewer schools, only three major Reformed seminaries participate, but it involves more funding over a longer period of time. The participating schools are Covenant Theological Seminary (the denominational seminary of the Presbyterian Church in America), Westminster Theological Seminary, and Westminster Seminary California.1

Just as with the COVID aid, federal loan participation is a matter of public record. Quarterly reports show how much of each kind of federal direct loans are disbursed through participating schools. I compiled the data of the three schools since 2020 into the following table:2

Total federal direct loans disbursed through these schools total nearly $9 million since 2020, with at least $2 million disbursed through each school. While this is but a molecule in the ocean of total federal educational lending, it likely represents a not-insignificant portion of these schools’ revenue and income.

It is no secret that if seminaries are going to operate, they need money. Salaries must be paid, facilities must be acquired, built, and maintained, the lights have to stay on, it’s not a simple or cheap enterprise. But not all money is created equally. When seminaries participate in any student loan programs, it means that students are indebting themselves to attend. This means that post-seminary life is going to require the graduate (if he graduates) to make payments, which can be large and lengthy depending on the amount and terms of the particular loans. Given that seminaries are private institutions, their tuition and fees are relatively high. At the time of posting, Covenant’s per-credit tuition was listed as $595, meaning that the full tuition cost of their 99-credit Master of Divinity (the standard educational credential for Reformed ministers) is $58,905. WSCAL’s 110-credit program at $495 per credit totals $54,450. WTS’ 111-credit MDiv will cost $136,530 in tuition at a whopping $1,230 per credit hour. Remember, this is just tuition, all housing, books, fees, and other associated costs are not included. For students who attend full-time and in-residence, this cost typically comes on top of having either no or limited paying employment. Now, there are scholarships and other financial aid to help mitigate some of these costs. Still, the fact that these loans are used means that not all of the costs are being met. For Covenant, the largest user of federal loans of the three, the equivalent to the tuition cost of 70 MDivs has been floated by federal money in the last 4 years.

Now, I have made some assumptions. Not everyone attending one of these schools is in a MDiv program and pursuing pastoral ministry. These schools all offer other degree options for other persons with other interests. But the main reason for the seminary is to train pastors, and pastors aren’t exactly known for getting the biggest paychecks after they graduate. This is not necessarily the fault of churches—many are small, have limited resources, and are doing the best they can to provide for their shepherds. Saddling ministers with massive debt before they ever have a ministerial call (if a call even comes) raises questions of fiscal responsibility. Debt limits the ability of ministers to serve in small churches or the mission field, as these cannot pay sufficiently to service large debts.

I think student debt is bad for everyone, and with very limited exceptions, no one should attend any school without a means to pay that doesn’t produce a mortgage without a house. However, I have an additional and particular concern here with the federal aspect of these loans. I argued in my piece on COVID money that, despite what many said and believed at the time, the money was not free. Even if there were no repayment requirements, the money came with some potentially troubling stipulations. There is never a free lunch, especially when Uncle Sam is buying.

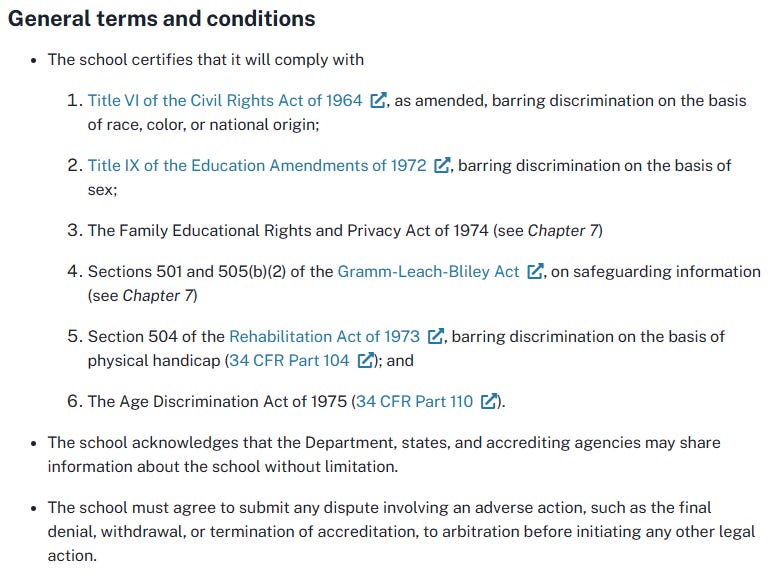

Federal student loans are quite similar. In order for a school to participate in federal aid programs, there is a lengthy and detailed application process. Among the many other stipulations for participation, the school must certify its compliance with various federal laws and regulations.

Of particular interest here is the certification of compliance with Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. This code has been interpreted by President Biden’s Department of Education, in light of the Bostock v. Clayton County decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, to protect against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.3 This is despite the fact that Title IX contains no such language, it only contains language about sex.

When I initially posted my findings on these student loans at these three schools and their conditions on Twitter last week, a certain former professor of mine accused me of breaking the ninth commandment and not having adequately done my research. It seems his primary concern centers around a religious institution exemption in Title IX. I was not, in fact, ignorant of that exemption. I did not include it in my short Twitter posts because ultimately, I don’t believe it matters that much. Similar religious exemptions in civil rights law have already failed to protect Christian humanitarian aid organization World Vision from a discrimination lawsuit brought on LGBT grounds. In fact, the exact exemption contained in Title IX was challenged by a recent class action lawsuit. While that lawsuit failed, if recent history has taught us anything about the lawfare of LGBT activists, they’ll be back, and after Christians and their institutions get buried in legal fees and court dates, all it takes is one federal judge having a bad day and the exemption is no more. Even Religion News Service ominously reported on that class action Title IX suit that it was “perhaps the first of several class-action suits against religious universities." In other words, activists see the Title IX exemption as a target, and the attack on it is likely not done.

Perhaps my professor and I could have had a productive discussion about whether or not the current regime will be bound by rule of law or the adequacy of protections against the current wave of LGBT activism in the current legal environment, but alas, he went for the ad hominem gun instead, and continued to fire it even after I provided these details.4

All of this to say, if the current regime seems bent on interpreting Title IX under Bostock’s revisionism, and if LGBT activists are willing to do the dirty work in court, it is not hard to see these conditions and self-certifications putting participating Christian schools in a very difficult position in the not-too-distant future. If a humanitarian organization like World Vision can be a target for lawfare, there is likely nothing about a seminary that would be found more sacred. These risks (along with the aforementioned problems of ministerial debt) perhaps explain why most Reformed seminaries do not participate in the federal loan program, and why at least one has left the program after previous participation.

Okay, you say, but seminaries need to get money from somewhere. This is true. As I said in my COVID money article, the seminaries’ turn to government money might show a deficiency in church financial support that needs to be remedied. But it may also be that seminaries could do a better job to live within their means. The complexity and comprehensiveness of federal programs often requires staff and man-hours to maintain compliance, which would be unnecessary outside of those programs. Maybe the old buildings will last a bit longer. Maybe the travel and special events can be trimmed. Maybe a direct model of denominational oversight and funding ought to be considered. Maybe churches can better train and vet prospective students so that there is less work for the seminaries to do. In negative world (to borrow from Aaron Renn’s taxonomy), Christians in all spheres may be called upon to make sacrifices. And, even if I grant (only for the sake of argument) that debt for seminary education is absolutely necessary, this can be obtained privately5 or seminaries can establish their own loan programs.6

Some readers may notice that this is now my third major foray into the world of seminaries and the legal and regulatory environment, after the COVID money and accreditation pieces. I can hear the questions coming now. “Why do you care so much about what is going on in seminaries?” The health of our churches is directly tied to the health of seminaries, and yet many of our seminaries seem to have formed some questionable entanglements with the city of man and adopted some questionable priorities. The interests of the church and modern academia are often not the same. The interests of laity in the church and of the federal government are certainly not the same. I’m a pastor who wants to see strong pastors and strong churches even as the church now lives and operates in negative world. Given my previous work in government, I know how to follow public records where they lead. “Why do you hate seminaries?” I don’t. Pastors need to be trained and educated, and good seminaries operating on sound principles can do the job. I have financially supported good seminaries. My current calling church financially supports good seminaries. But seminaries need to be good. Shouldering pastors and churches with debt is not good. Leaving open doors for hostile governments, NGOs, and activists to influence the seminary’s agenda is not good. Seminaries need to act in a manner worthy of the support and trust that churches and donors have placed in them. “Don’t you have better things to do?” Yeah, probably. Combing through government records and legal documents isn’t the most riveting of work, and I’d rather be free to do ministry work and attend to other cares knowing that the seminaries are taking care of their own business. But I sense that too few within seminaries and loyal to them understand the times in which they live, the risks they face, and the blind spots they have. If we are not diligent to guard and protect the church and her institutions, we may find ourselves having lost them, as many before us have.

While I did not include them in my analysis, there were several other prominent evangelical seminaries that I noticed were participating in the federal loan program, such as Dallas Theological Seminary, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, The Master’s Seminary, and Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. Several Christian undergraduate institutions participate as well. Those with an interest in these institutions may wish to review the data and inquire further.

Compiled from quarterly loan volume data at https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/title-iv#loan-volume. My calculations are shown here. These figures are a total of unsubsidized graduate, and Grad Plus loans disbursed to the three schools in those periods. There are a few undergraduate loans that were also issued, but their amount is relatively small. I chose 2020 as a start time because as this was the year of COVID, BLM riots, and the election of President Joe Biden, it seemed to be a year of a turning over of a new era in church-state relations in America.

https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-department-education-confirms-title-ix-protects-students-discrimination-based-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity. An injunction has restricted the Department of Education from enforcing this order against public schools in several states, but it is unclear where higher education stands in this. At a minimum, it betrays the department’s intentions, consistent with President Biden’s day-one executive order to standardize all agency policy according to Bostock’s precedent. This means that all federal programs, not just educational ones, pose new hazards to Christian organizations.

According to their website, this is the practice of Reformed Theological Seminary. https://rts.edu/admissions/financial-aid/

Knox Theological Seminary’s fixed payment plan is an example of this, as they front the tuition cost of the program, and the student makes fixed monthly installment payments during and after. https://www.knoxseminary.edu/tuition